Railroads Before There Were Railroads (The Invention of Railroads Before 1830: The Dawn of a New Era)

The invention of railroads before 1830 marked the beginning of a transportation revolution that would transform economies, societies, and landscapes across the world. Railroads emerged from the combination of several critical innovations, most notably the development of the steam engine and early rail systems in Great Britain. This essay explores the history of railroads up to 1830, focusing on their origins, the technological advancements that made them possible, and the socio-economic impact they began to have.

An illustrated historical landscape depicting the early invention of railroads before 1830. The scene features a steam-powered locomotive in an English countryside.

The Early Origins of Railroads

Railroads did not emerge in a vacuum; they evolved from earlier transportation systems and technologies. As early as the 16th century, miners in Germany and England used rudimentary wooden tracks to move heavy loads of coal and ore from mines to nearby storage or transport points. These early systems, known as wagonways, were not powered by engines but by animals or human effort.

The use of iron in these tracks began in the early 18th century, which improved durability and allowed for heavier loads. By the mid-18th century, cast iron rails had replaced wooden ones in many locations, particularly in Britain, which was experiencing a growing demand for coal due to the Industrial Revolution. These wagonways laid the foundation for the development of railroads by demonstrating the benefits of fixed tracks for reducing friction and easing the transportation of heavy goods.

The Development of the Steam Engine

The railroad’s most transformative innovation was the steam engine. The steam engine, invented by Thomas Newcomen in 1712 and significantly improved by James Watt in the 1760s and 1770s, was initially designed for pumping water out of mines. Newcomen’s engine was a relatively crude machine, operating with low efficiency, but it was revolutionary in using steam power to perform mechanical work.

James Watt’s innovations, including the separate condenser and the rotary motion, made the steam engine much more efficient and versatile. Watt’s engines became widely used in industry, driving machinery in textile mills and other factories. However, the potential for steam engines as a motive power for transportation remained largely unexplored until the late 18th century.

Richard Trevithick and the First Steam Locomotives

The leap from stationary steam engines to locomotion was made by Richard Trevithick, a British inventor and engineer. In 1804, Trevithick built the first full-scale working steam locomotive. His machine, known as the “Penydarren locomotive,” was designed to haul loads along an iron track at a Welsh ironworks. While the locomotive successfully carried ten tons of iron and seventy passengers on its inaugural journey, it faced significant challenges. The track was not strong enough to support the heavy locomotive, and the venture was ultimately deemed impractical.

Despite its limitations, Trevithick’s invention demonstrated the feasibility of steam-powered locomotion and inspired further experimentation. His work laid the groundwork for others to refine the concept and overcome its early technical hurdles.

George Stephenson: The Father of Railways

The true pioneer of practical railroads was George Stephenson, a British engineer often referred to as the “Father of Railways.” Stephenson recognized the potential of steam-powered locomotion and dedicated his career to improving the technology and building the infrastructure necessary for its success.

In 1814, Stephenson built his first locomotive, named Blücher, which was used to haul coal at a colliery near Newcastle. Unlike Trevithick’s earlier designs, Stephenson’s locomotive was more reliable and better suited to the iron tracks of the time. He continued to refine his designs, focusing on improvements to the engine’s power, efficiency, and durability.

Early British Railways

One of the most significant milestones in the history of railroads was the opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825. This railway, designed to connect the coal mines of County Durham with the port of Stockton-on-Tees, was the first public railway to use steam locomotives.

George Stephenson served as the chief engineer for the project, and his locomotive, Locomotion No. 1, was used on the inaugural journey. The Stockton and Darlington Railway was a hybrid system, as it also accommodated horse-drawn wagons and stationary steam engines for certain segments. Nevertheless, it marked a turning point in transportation history by proving the viability of steam-powered railroads for commercial purposes.

The success of the Stockton and Darlington Railway set the stage for the development of more ambitious projects. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway, opened in 1830, was the first railway designed to transport both passengers and freight using steam locomotives exclusively. This railway connected two of Britain’s most important industrial cities, facilitating the movement of raw materials, finished goods, and people.

George Stephenson once again played a central role in this project, serving as the chief engineer. During the railway’s construction, Stephenson faced numerous challenges, including the need to build sturdy bridges, excavate tunnels, and lay tracks across uneven terrain. The completion of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was a triumph of engineering and logistics.

The railway’s official opening featured a competition to determine the best locomotive for the line. Stephenson’s Rocket won the contest, demonstrating superior speed, reliability, and efficiency. The Rocket became a symbol of the new era of rail transportation, reaching speeds of up to 30 miles per hour—a remarkable achievement at the time.

The Socio-Economic Impact of Early Railroads

The invention of railroads had far-reaching consequences, even in their earliest stages. By 1830, railroads were already beginning to reshape societies and economies, particularly in Britain.

Railroads revolutionized transportation by significantly reducing the cost and time required to move goods and people. This efficiency was particularly beneficial to industries such as coal mining, manufacturing, and agriculture. Coal, which had previously been transported by slow-moving barges or horse-drawn carts, could now be delivered quickly and cheaply to urban centers and industrial hubs.

Railroads also facilitated the growth of markets by connecting previously isolated regions. Farmers and manufacturers could sell their goods to a wider audience, leading to increased productivity and economic growth. The railroads themselves became major industries, creating jobs in construction, engineering, and operation.

Railroads began to change the way people lived and interacted. The ability to travel quickly and affordably opened up new opportunities for work, leisure, and education. For the first time, ordinary people could travel significant distances, whether to visit relatives, attend events, or explore new regions.

The railroads also played a role in urbanization by making it easier for people to commute to cities for work. This trend contributed to the growth of industrial towns and the expansion of urban areas. The increased mobility enabled by railroads helped to break down regional barriers and foster a sense of national identity.

The early railroads spurred innovation in numerous fields, from civil engineering to metallurgy. The need for durable tracks, powerful locomotives, and efficient signaling systems drove technological progress, setting the stage for further advancements in transportation and industry.

A Short History of “Named” Locomotives

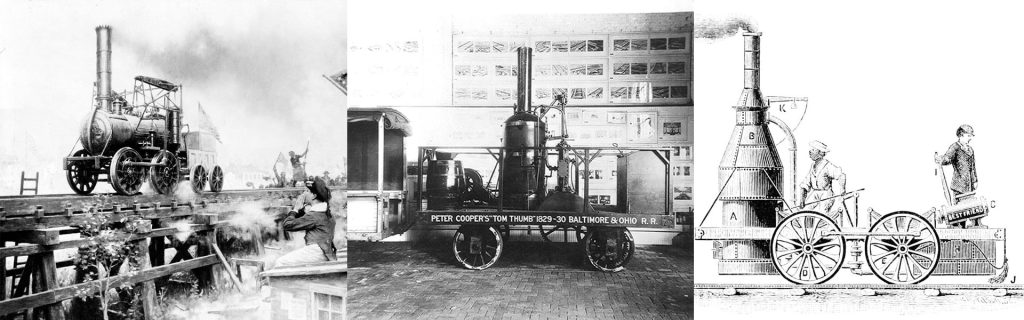

The Stourbidge Lion (1829), The Tom Thumb (1829) and The Best Friend of Charleston (1830)

The Stourbridge Lion was a railroad steam locomotive. It was the first locomotive and the first foreign built locomotive to be operated in the United States, and one of the first locomotives to operate outside Britain. It takes its name from the lion’s face painted on the front, and Stourbridge in England, where it was manufactured by the firm Foster, Rastrick and Company in 1829. The locomotive, obtained by the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company (D&H), was shipped to New York in May 1829, where it was tested raised on blocks. It was then taken to Honesdale, Pennsylvania for testing on the company’s newly built track. The locomotive performed well in its first test in August 1829, but was found to be too heavy for the track and was never used for its intended purpose of hauling coal wagons. During the next few decades, a number of parts were removed from the abandoned locomotive until only the boiler and a few other components remained. These were acquired by the Smithsonian Institution in 1890 and are currently on display at the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore.

Tom Thumb was the first American-built steam locomotive to operate on a common-carrier railroad. It was designed and constructed by Peter Cooper in 1829 to convince owners of the newly formed Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) (now CSX) to use steam engines; it was not intended to enter revenue service. It is especially remembered as a participant in a legendary race with a horse-drawn car, which the horse won after Tom Thumb suffered a mechanical failure. However, the demonstration was successful, and the railroad committed to the use of steam locomotion and held trials in the following year for a working engine.

The Best Friend of Charleston was a steam-powered railroad locomotive widely considered the first locomotive to be built entirely within the United States for revenue service. It was also the first locomotive to suffer a boiler explosion in the United States. The locomotive was built for the South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company by the West Point Foundry of New York in 1830. Disassembled for shipment by boat to Charleston, South Carolina, it arrived in October of that year and was unofficially named The Best Friend of Charleston. After its inaugural run on Christmas Day, it was used in regular passenger service along a six-mile demonstration route in Charleston. At the time, it was considered one of the fastest modes of transport, taking its passengers “on the wings of wind at the speed of fifteen to twenty-five miles per hour.”

The DeWitt Clinton of the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad (M&H) was an American steam locomotive and the first working steam locomotive built for service in New York state. The locomotive was built in 1831 and began operations the same year. It was named in honor of DeWitt Clinton, the governor of New York State responsible for the Erie Canal, a competitor to the railroad. Portions of the steam engine were cast at the West Point Foundry in Cold Spring, New York. The DeWitt Clinton’s first run was from the city of Albany, New York, to Schenectady, New York, a run of 16 or 17 miles. Its passenger cars were made of stagecoach bodies in which riders would sit either inside or on outdoor rumble seats. The cars were known as Goold cars and were named after coach builder James Goold of Albany.

Conclusion

The invention of railroads before 1830 was a transformative period in human history, characterized by groundbreaking technological innovations and far-reaching socio-economic changes. From the humble beginnings of wooden wagonways to the triumph of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the development of railroads demonstrated the power of human ingenuity and the potential of steam power to revolutionize transportation.

The early railroads laid the foundation for a global transportation network that would drive economic growth, connect distant regions, and shape modern societies. While the railroads of the pre-1830 era were limited in scope compared to the vast systems that would emerge later in the 19th century, their significance cannot be overstated. They represent the dawn of a new era in which speed, efficiency, and connectivity became defining features of the modern world.