Bridging Horizons: The Erie Railroad’s Path of Innovation

The Erie Railroad, one of the earliest and most influential railroads in the United States, was established to link the Atlantic seaboard with the interior of the country. Formed in the early 19th century, its history illustrates the pivotal role of rail transport in shaping American industry, commerce, and settlement patterns. Spanning nearly a century, the Erie Railroad’s development was marked by ambitious expansion, fierce competition, and significant financial challenges, all of which contributed to the railroad’s transformation from a regional line to an influential player in the national transportation network. This essay explores the Erie Railroad’s formation, expansion, and operational struggles through 1920.

The Early Beginnings of the Erie Railroad

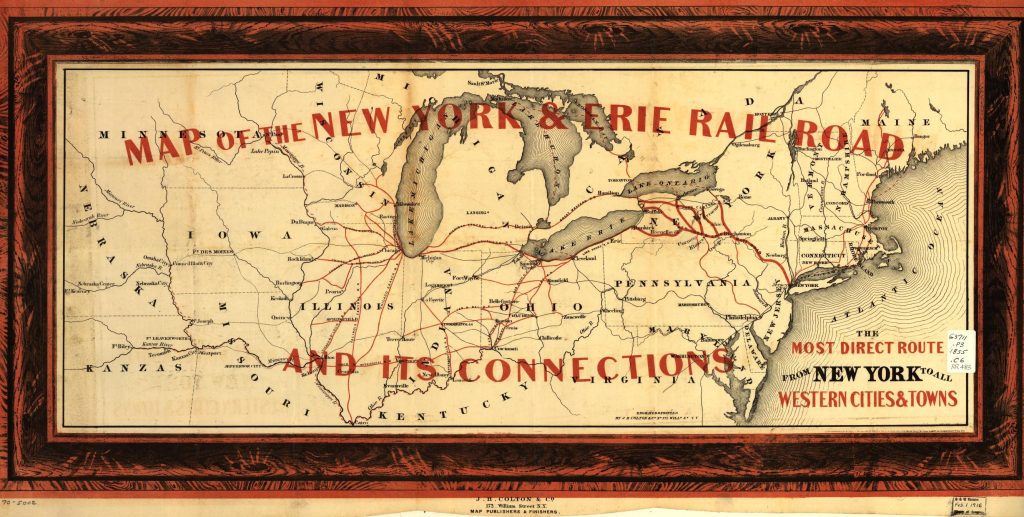

The Erie Railroad was born out of a desire to provide a reliable transport route between New York City and Lake Erie, with the broader goal of linking the Great Lakes region to the Eastern Seaboard. New York merchants and business leaders recognized that an effective transportation link could facilitate access to the vast agricultural and mineral resources of the Midwest, fostering economic development in both regions.

The idea for the Erie Railroad took root in the 1820s, during a period of burgeoning interest in canal and rail systems. The Erie Canal, completed in 1825, had demonstrated the potential for improved transport infrastructure, and regional leaders saw the value in connecting New York City to Lake Erie by rail. The New York and Erie Railroad was chartered by the New York State Legislature in 1832, with a mandate to construct a line spanning from Piermont, New York, on the Hudson River, to Dunkirk on Lake Erie. The charter stipulated the use of a six-foot gauge, wider than the standard four-foot-eight-and-a-half-inch gauge, which allowed for greater stability in hauling heavy freight but ultimately limited interoperability with other rail lines.

The construction of the line was a monumental task, fraught with financial and engineering challenges. Early railroad technology was in its infancy, and the costs of constructing a rail line across rugged terrain were significant. Fundraising was difficult, as investors were wary of the high costs and uncertain returns. Nevertheless, the company pressed forward, breaking ground in the early 1830s. Initial construction was slow, and the company faced multiple bankruptcies and reorganizations. By 1841, however, the first segment of the Erie Railroad was completed, running from Piermont to Goshen, New York. The line reached its intended terminus at Dunkirk in 1851, nearly two decades after the railroad’s founding.

The Erie Railroad’s Expansion and Economic Impact

With its route completed, the Erie Railroad quickly became a crucial transportation artery. It connected agricultural regions in the Midwest with markets on the East Coast, allowing farmers and merchants to move goods quickly and efficiently. The Erie played a vital role in transporting grain, timber, and livestock eastward, while manufactured goods flowed westward, fueling settlement and economic expansion across the Northern United States.

During the 1850s and 1860s, the Erie expanded further, seeking to capitalize on its strategic position. The company acquired several smaller railroads to enhance its network, extending its reach into Pennsylvania and Ohio. In particular, the Erie’s access to Pennsylvania’s coal-rich regions gave it a valuable commodity to transport, contributing to the line’s financial stability and profitability. However, competition with other railroads, notably the New York Central Railroad, began to intensify. This rivalry set the stage for one of the most famous battles in American railroad history: the Erie War.

The Erie War and Wall Street Intrigue

In the 1860s, the Erie Railroad became embroiled in a fierce struggle for control involving some of the most prominent figures of Wall Street. Jay Gould, Daniel Drew, and James Fisk—collectively known as the “Erie Ring”—maneuvered to seize control of the Erie Railroad, which they saw as a lucrative prize in the increasingly competitive rail industry. Their chief rival was Cornelius Vanderbilt, head of the New York Central Railroad, who sought to consolidate his control over rail routes in the Northeastern United States.

In 1867, Vanderbilt attempted a hostile takeover of the Erie Railroad by purchasing large quantities of its stock. In response, Drew, Fisk, and Gould used their control of the Erie’s board of directors to issue additional shares of stock, diluting Vanderbilt’s holdings and thwarting his takeover attempt. This tactic led to a legal battle that attracted public attention and highlighted the lack of regulation in American finance at the time. Gould and his associates ultimately retained control of the Erie, although their tactics damaged the company’s reputation and finances. The Erie War epitomized the “robber baron” era of American industry, during which financiers used aggressive and often unethical tactics to amass wealth and control.

Technological and Operational Developments

Throughout the late 19th century, the Erie Railroad continued to grow and modernize. Advances in rail technology allowed the Erie to improve its infrastructure, including replacing its original wooden rails with steel ones and upgrading locomotives to more powerful models capable of hauling heavier loads. The Erie also began converting sections of its track to the standard gauge, allowing it to connect with other rail lines and facilitating interline freight transfers. By the 1880s, the Erie was fully integrated into the national rail network, allowing goods to move seamlessly between it and other lines.

The Erie also made strides in passenger service, offering comfortable accommodations on its long-distance trains. The introduction of Pullman sleeping cars on the Erie’s routes enabled passengers to travel overnight, further enhancing the railroad’s appeal. In addition to passenger service, the Erie developed extensive freight facilities in cities such as Jersey City, New Jersey, where it established large yards and terminals to handle the increased volume of goods flowing through its network.

Financial Difficulties and Reorganizations

Despite its growth, the Erie Railroad faced persistent financial challenges. The high costs of construction, combined with intense competition and periods of economic downturn, left the Erie with a heavy debt burden. The company underwent several bankruptcies and reorganizations during the late 19th century as it struggled to balance expansion with profitability.

One of the most significant reorganizations occurred in 1895, when the Erie was taken over by J.P. Morgan and a group of other financiers. Morgan’s influence marked the beginning of a new era for the railroad, as he implemented measures to improve its financial stability. Under Morgan’s leadership, the Erie reduced its debt, cut operating costs, and focused on improving service quality. Despite these efforts, however, the Erie continued to struggle with profitability, a situation exacerbated by the increasingly saturated rail market and the rise of competing transportation modes, such as automobiles and trucks.

The Erie Railroad in the Early 20th Century

At the dawn of the 20th century, the Erie Railroad faced a changing transportation landscape. The rise of automobiles and trucks began to erode the railroad’s dominance in the freight and passenger markets, particularly for short-haul traffic. Additionally, new federal regulations, including the Interstate Commerce Act and the Sherman Antitrust Act, imposed constraints on railroad operations and limited the Erie’s ability to engage in practices such as rate discrimination.

During World War I, the Federal government temporarily nationalized the railroads to ensure efficient transportation of troops and supplies. The Erie, along with other major railroads, came under the control of the United States Railroad Administration (USRA). While the government’s control helped improve efficiency during the war, it also highlighted the inefficiencies and financial challenges facing the railroad industry. The Erie struggled to maintain profitability during this period, as its operating costs rose, and its debt burden continued to weigh heavily on its finances.

Following the war, the Erie Railroad resumed private operation but faced a difficult postwar economy. The railroad sought to adapt to the changing market by investing in modernization, including the electrification of some sections of track and the introduction of diesel locomotives. These efforts were only partially successful, as the Erie continued to face financial difficulties and declining passenger numbers.

The Legacy of the Erie Railroad by 1920

By 1920, the Erie Railroad had cemented its place in American history as one of the nation’s most important railroads. Its route from New York City to Lake Erie had helped to open the Midwest to settlement and industry, and its role in the Erie War had highlighted the need for regulatory reform in American finance and industry. The Erie’s influence extended beyond transportation, as it contributed to the economic development of the regions it served, fostering trade and industry in towns and cities along its route.

However, the Erie’s legacy was also marked by financial instability and the challenges of adapting to a rapidly changing transportation environment. The railroad’s struggles reflected the broader difficulties faced by the American rail industry, which was grappling with regulatory pressures, labor disputes, and competition from emerging technologies.

In conclusion, the history of the Erie Railroad up through 1920 illustrates the transformative impact of railroads on American society and economy. From its beginnings as an ambitious project to link the Atlantic coast with the Great Lakes, the Erie evolved into a major transportation artery that helped shape the economic landscape of the Northeastern and Midwestern United States. Although it faced significant financial and operational challenges, the Erie Railroad played a crucial role in the development of the American rail industry and left an enduring legacy that continues to be felt in the regions it once served.