The inception and subsequent rise of American railroads from 1830 to the start of the Civil War in 1860 marked a pivotal era in the United States, catalyzing profound economic, social, and geographic transformations. This period, often referred to as the “railroad revolution,” saw the fledgling American railroad industry evolve from experimental locomotive carriages on wooden tracks to an expansive steel web that connected distant corners of the nation. This essay delves into the early development, rapid expansion, and profound impact of railroads, weaving through the technological advancements, economic incentives, and sociopolitical changes that the railroad industry prompted during its formative years.

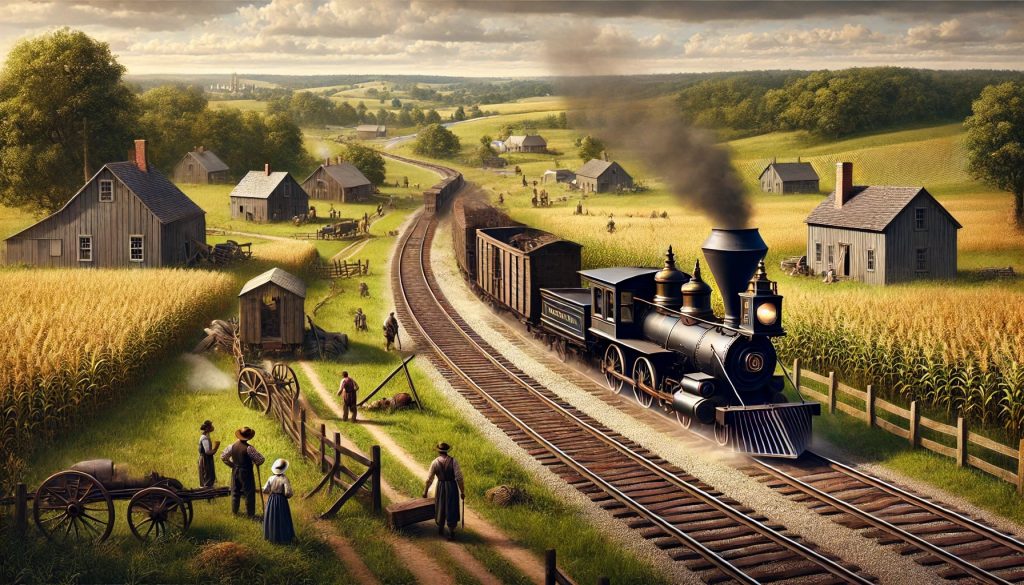

A highly styled but historically accurate image of American railroading circa 1850.

The Early Beginnings: 1830-1840

Rail transportation in America was inspired by the successful rail networks in England, where steam locomotives had begun revolutionizing goods and passenger movement. The United States, with its vast distances and rugged landscapes, presented both a formidable challenge and a vast opportunity for this emerging mode of transportation. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O), chartered in 1827, laid its first stone in 1828 and by 1830 had completed 13 miles of track, officially becoming the first operational railroad in the U.S. This pioneering project set the stage for the adoption and adaptation of rail technology across the country.

The 1830s witnessed a surge in railroad charters and construction. The Charleston & Hamburg line in South Carolina, for instance, stretched over 136 miles by 1833, becoming the longest continuous railroad in the world at that time. The burgeoning railroad industry was propelled not only by the promise of economic gain but also by the strategic need to bind the burgeoning nation together, especially as the push westward and the burgeoning cotton economy in the South intensified the demand for efficient transportation routes.

Technological Innovations and Adaptations

The rapid expansion of railroads was accompanied by significant technological advancements. Initially, American engineers faced numerous mechanical and engineering challenges, including primitive locomotive designs and unreliable track infrastructure. Early tracks were made of wooden planks, which were prone to rot and breakage. The introduction of the T-rail – a design that used a flat bottom rail made of iron – and the adoption of a standard gauge significantly improved the durability and reliability of railroad tracks.

Locomotives, too, underwent rapid improvements. The Tom Thumb, built by Peter Cooper in 1830, demonstrated the superiority of steam-powered locomotion over horse-drawn carriages, even if it famously lost a race to a horse due to mechanical failure. The design and efficiency of locomotives improved swiftly, with features like multi-tubular boilers and more effective steam cylinders enhancing speed and fuel efficiency.

Economic Expansion and Impact

Railroads quickly became the backbone of American economic expansion. They facilitated the large-scale transportation of agricultural products from the Midwest to eastern markets, significantly lowering food costs and fueling urban growth. Industrial sectors such as coal, steel, and timber saw unprecedented demand, stimulated by railroad expansion needs. Railroads themselves became major employers, drawing labor from an influx of European immigrants and rural Americans leaving farms for opportunities in urban centers.

The rise of railroads also stimulated financial innovation, including the development of complex financing models, stock issuance, and the establishment of modern management structures. However, the sector was also marred by speculation and instability, evidenced by the Panic of 1837 and later financial crises, which were exacerbated by overinvestment and speculative funding in railroads.

Sociopolitical Changes and Challenges

As railroads redefined the economic landscape, they also had profound sociopolitical impacts. They were instrumental in the internal improvement debates, influencing federal and state policies on infrastructure and land grants. The legal landscape adjusted to new realities as well, dealing with issues of corporate law, private property, and the eminent domain necessary for track laying.

The expansion of railroads further intensified the slavery debate in America. As the cotton economy boomed, thanks to more efficient inland transportation, the South’s reliance on slave labor increased, heightening tensions between abolitionist northern states and pro-slavery southern states. Railroads, thus, inadvertently became intertwined with the sectional conflicts that would eventually lead to the Civil War.

Conclusion

By 1860, the United States boasted over 30,000 miles of track, laying the groundwork for industrial supremacy and modern economic development. The period between 1830 and 1860 was not merely about the growth of a transportation system; it was a transformative era that reshaped America’s economic structures, labor systems, and even its very societal fabric. As the Civil War approached, railroads had already become an integral part of the American landscape, symbolizing both the immense potential and the profound challenges of a rapidly industrializing nation. The “iron horse” had not only conquered the vast American terrain but had also redefined the path of American progress, setting the stage for the complex and turbulent years that would follow.