In the annals of American transportation history, few regions embraced the iron horse as eagerly as the South in the early 19th century. Among the pioneers was the Charleston and Hamburg Railroad—an ambitious venture born from necessity and vision. Its legacy would help forge one of the most significant rail systems in the southeastern United States: the Southern Railway.

The Charleston and Hamburg Railroad: A Bold Southern Experiment

In the 1820s, Charleston, South Carolina, faced economic stagnation. Once a bustling port and commercial center, it was increasingly sidelined as trade routes shifted westward and cotton moved through ports like Savannah and New Orleans. Inland towns were thriving while Charleston’s prosperity waned. City leaders realized they needed to reassert Charleston’s relevance by tapping into the burgeoning cotton-rich interior of South Carolina and Georgia.

Enter the Charleston and Hamburg Railroad Company. Chartered in 1827 by the South Carolina General Assembly, the railroad aimed to connect Charleston to Hamburg, a small town across the Savannah River from Augusta, Georgia—136 miles inland. This was a radical idea: the longest railroad in the world at the time was just over 25 miles. Critics called the project insane; supporters called it inspired.

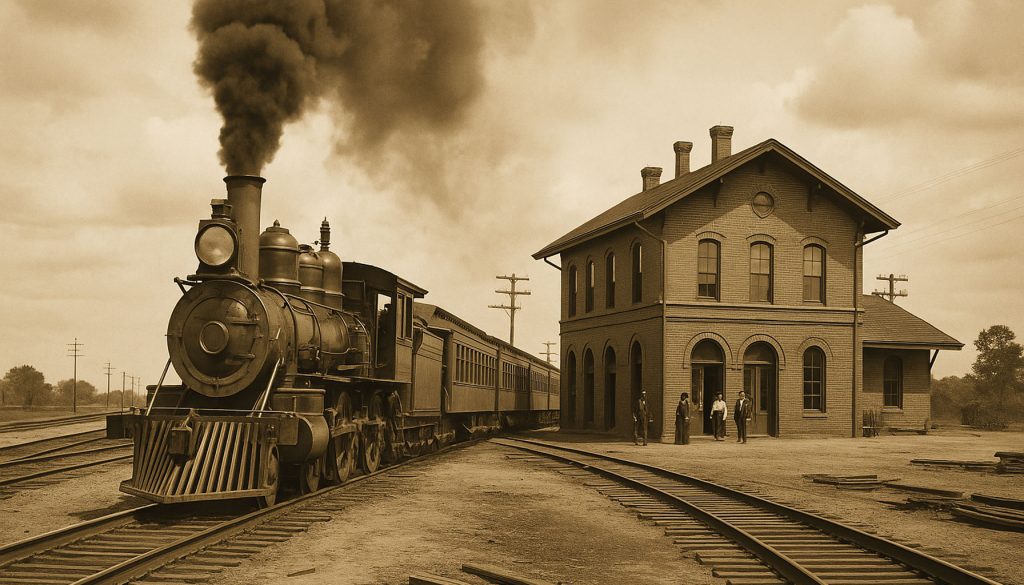

Under the guidance of engineer Horatio Allen, construction began in 1830. Allen had previously studied rail systems in England and brought a practical vision to the project. The railroad was built on a single track using strap iron rails affixed to wooden beams, and initially operated with horse-drawn carriages. However, the adoption of steam locomotion quickly followed.

On Christmas Day in 1830, the railroad launched its first steam-powered locomotive: the Best Friend of Charleston. Built in the United States, it was among the first locomotives to operate regularly on an American railroad. Its maiden run, though short, symbolized a technological leap forward for the South.

By 1833, the full 136-mile route from Charleston to Hamburg was complete. At that time, it was the longest regularly operated railroad under single management in the world. The Charleston and Hamburg Railroad had demonstrated the potential of railroads to overcome natural obstacles, move freight efficiently, and transform economies.

A Catalyst for Economic Development

The railroad became a critical artery for the South Carolina economy. Planters could now send their cotton to Charleston’s port with far greater speed and reliability than via river or wagon. Inland towns like Aiken, which sprang up along the line, flourished.

The Charleston and Hamburg line helped standardize rail technology in the region and inspired further rail expansion across the South. But it was not without its flaws. The wooden rail beds were fragile, maintenance was expensive, and early locomotives often failed under pressure. Still, the potential was unmistakable.

The company later merged and reorganized under the South Carolina Canal and Railroad Company. Over the ensuing decades, it suffered financial troubles, partly due to poor management and partly due to the Civil War’s devastation. But the infrastructure it built remained valuable, and the line would eventually be absorbed into a growing regional network that would culminate in the Southern Railway.

Birth of the Southern Railway: Post-War Reconstruction and Consolidation

The Civil War decimated Southern railroads. Lines were destroyed, rolling stock burned, and bridges wrecked. Following the war, the South’s railroads were patchwork systems—fragmented and undercapitalized. Yet in this adversity lay an opportunity.

As the South rebuilt, a new wave of consolidation swept across the region. Investors, particularly from the North, began acquiring and merging smaller lines to create more efficient systems.

One of the key figures in this transformation was J.P. Morgan, the powerful financier who recognized the potential of a unified Southern rail network. In the 1890s, he orchestrated a series of mergers that would give birth to the **Southern Railway Company** in 1894. The new system was built around the Richmond and Danville Railroad and the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railroad, among others.

The Charleston and Hamburg line, by this time part of the South Carolina and Georgia Railroad, was absorbed into this growing conglomerate. The Southern Railway inherited its infrastructure, right-of-way, and legacy. What had begun as a single-state venture now became part of a 4,000-mile system stretching across the American Southeast.

Southern Railway in the Early 20th Century: A System of Steel and Strategy

By the turn of the 20th century, the Southern Railway was more than just a transportation network—it was an agent of regional development. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., with operations throughout Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee, the Southern Railway connected rural cotton fields, coal mines, textile mills, and urban markets.

Industrial Expansion and Modernization

Under the leadership of President Samuel Spencer, Southern Railway adopted a modern, business-oriented approach to railroading. Spencer famously emphasized cooperation between the railroad and regional industries. “The prosperity of the railroad depends on the prosperity of the territory it serves,” he often said.

This philosophy translated into significant investments in infrastructure. Southern Railway upgraded its lines with steel rails, improved signaling systems, and built more powerful locomotives. Bridges were reinforced or replaced, and maintenance standards improved dramatically.

Freight traffic, especially cotton, coal, and timber, became the railroad’s lifeblood. Southern Railway also developed key passenger routes, offering connections between major cities like Atlanta, Birmingham, Charlotte, and Washington, D.C. Elegant passenger trains such as the *Piedmont Limited* and the *Crescent* became icons of comfort and speed.

Innovation and Standardization

Southern Railway was among the leaders in implementing standard gauge tracks (4 feet, 8.5 inches) across its entire system, a vital step that allowed for seamless interchange with other railroads. It also modernized its rolling stock, investing in refrigerated cars for fruit and vegetables, tank cars for chemicals, and high-capacity hoppers for coal.

It was also forward-thinking in its use of technology. By the 1910s, the railroad had begun experimenting with electric locomotives and centralized traffic control systems. In 1914, Southern established a testing laboratory in Alexandria, Virginia, to study metallurgy, rail durability, and engine performance—reflecting a corporate culture grounded in engineering excellence.

Impact on Southern Society

Southern Railway’s influence extended beyond the rails. It helped modernize the South’s economy and integrate rural communities into national markets. The company employed thousands and indirectly supported tens of thousands more through industries that relied on reliable transportation: mining, textiles, agriculture, and manufacturing.

Towns with depots often flourished into hubs of commerce and culture. Southern Railway also played a critical role in African American labor history. Many Black workers were employed as porters, brakemen, and laborers, navigating the complexities of Jim Crow segregation while forming the backbone of the company’s operations. Their stories form an important part of Southern Railway’s legacy.

Challenges and Resilience

Despite its progress, Southern Railway faced headwinds. The rise of the automobile and improved road systems began to erode passenger traffic. Labor unrest, particularly the Great Railroad Strike of 1922, impacted operations. The company also endured the financial shocks of World War I and the postwar recession.

But the Southern Railway proved adaptable. It focused increasingly on freight efficiency, reducing costs, and optimizing routes. It forged partnerships with major industries and invested in research to increase hauling capacity. By the 1920s, it remained one of the South’s most financially stable and technologically advanced railroads.

A Legacy in Motion

The story of the Charleston and Hamburg Railroad is a story of vision—of a group of civic leaders who dared to challenge geographic limitations to preserve economic relevance. Their gamble laid the groundwork for a transportation revolution in the South.

The Southern Railway, inheriting that legacy, became a pillar of Southern development. Through investment, modernization, and strategic consolidation, it helped transform a war-torn, agrarian region into a more diversified, interconnected economic engine.

In 1982, the Southern Railway merged with the Norfolk and Western Railway to form Norfolk Southern Corporation—a modern Class I railroad that continues to play a vital role in American freight logistics.

But long before that corporate merger, before diesel locomotives and computer-aided dispatching, it all began with a few miles of wooden rails laid across the South Carolina countryside—and a locomotive called the *Best Friend of Charleston* chugging toward a future still being written.