The history of railroads is often associated with the revolutionary steam-powered locomotives of the early 19th century, but the concept of railroad-like systems predates the era of George Stephenson’s “Rocket” and other iconic steam engines. Before the railroads as we know them emerged, societies utilized various transportation systems that laid the groundwork for modern railways. These early endeavors, spanning centuries and multiple continents, were powered by diverse means, ranging from human and animal labor to gravity and rudimentary mechanical systems. This essay explores these precursors to railroads, highlighting their evolution, uses, and the innovative technologies that made them possible.

Ancient Trackways: The Earliest Predecessors

The earliest known examples of railroad-like systems date back to ancient civilizations, particularly in Greece and Rome. Around 600 BCE, the Greeks constructed the Diolkos, a paved trackway near Corinth, used to transport ships across the Isthmus of Corinth. The Diolkos consisted of grooved limestone tracks, along which carts moved ships on rollers. These carts were likely pulled by human or animal power, showcasing one of the first instances of guided transportation. This system—though not a railway in the modern sense—demonstrated the utility of predetermined paths for the movement of heavy loads.

Similarly, the Roman Empire developed advanced road networks and implemented track systems for mining and quarrying. Wooden or stone tracks were used in mines to facilitate the movement of ore-laden carts. These tracks ensured smoother operations and minimized friction compared to unpaved surfaces. In these applications, the carts were typically powered by human labor or animals such as donkeys or oxen, emphasizing the role of guided paths in improving efficiency.

The Advent of Wagonways in Medieval Europe

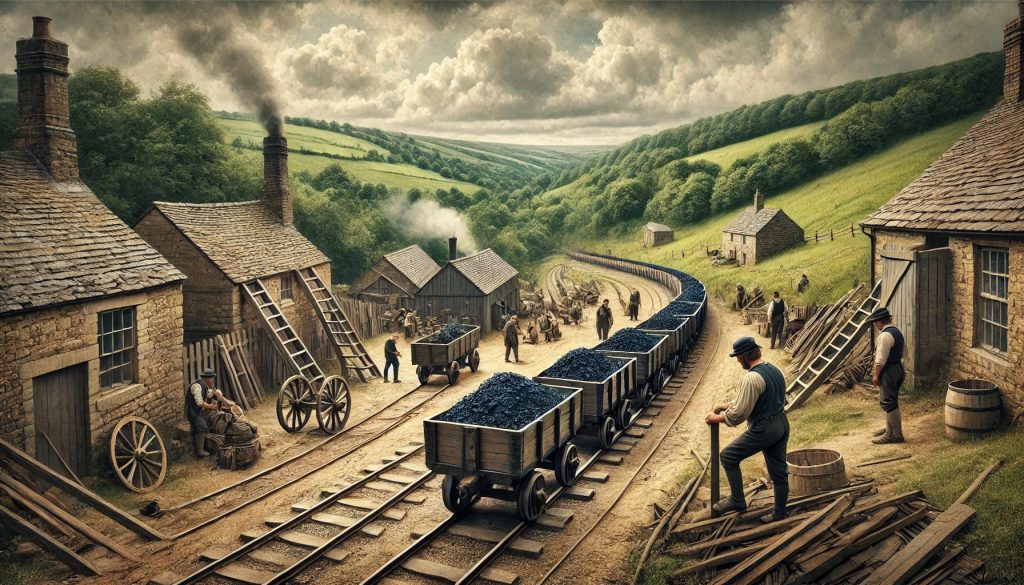

During the late medieval period, technological advancements in mining led to the development of wagonways, a significant precursor to modern railroads. Wagonways emerged in Europe around the 16th century, particularly in Germany and England, where mining activities required efficient methods to transport heavy materials like coal and ore over uneven terrain.

These wagonways consisted of wooden rails upon which carts with flanged wheels could travel. Flanges—the raised edges on wheels—helped keep the carts aligned on the rails, reducing the risk of derailment and minimizing energy loss. Initially, these systems relied on animal power, with horses or oxen pulling the carts along the rails. The guided paths allowed the animals to exert less effort compared to hauling loads over dirt roads, significantly increasing productivity.

One notable example of early wagonways was the Wollaton Wagonway, built in Nottingham, England, in 1604. This system connected a coal mine to a canal, enabling the efficient transportation of coal. The wooden rails eventually evolved into iron-topped rails, which were more durable and better suited to heavy loads.

The Transition to Plateways and Iron Rails

As wagonways gained popularity, engineers sought to improve their durability and load-bearing capacity. By the 18th century, wooden rails were increasingly replaced with iron rails, leading to the development of plateways. Plateways featured flat iron plates as rails, often with raised edges to guide the wheels of the carts. These systems were more robust than their wooden predecessors and could handle heavier loads, making them ideal for industrial applications.

Plateways also introduced a new level of standardization in track design. For example, the Coalbrookdale Company in Shropshire, England, adopted iron plateways in the mid-1700s to transport coal from mines to the River Severn. This innovation not only increased the efficiency of coal transportation but also set the stage for the widespread use of iron rails in later railroads.

These systems continued to rely on animal power, but some began incorporating mechanical aids. For instance, stationary winches powered by water wheels or manually operated capstans were used to pull carts up steep inclines. This combination of animal and mechanical power highlighted the growing ingenuity in pre-railroad transportation systems.

Gravity Railways: Harnessing Natural Forces

Gravity railroad in England from the late 1700s. The scene shows a rustic setting with the track running down the hill.

Another significant precursor to modern railroads was the gravity railway, which utilized the force of gravity to move carts along inclined tracks. These systems were particularly common in mining regions, where carts loaded with heavy materials could descend from higher elevations to processing areas or ports with minimal external power.

One early example of a gravity railway was the Haytor Granite Tramway in Devon, England, built in 1820. This system used granite rails to guide carts transporting granite blocks from quarries to a canal. While gravity facilitated the descent of loaded carts, animals or manual laborers were required to haul the empty carts back uphill. The efficiency of gravity railways depended heavily on the topography of the region, making them ideal for hilly or mountainous areas.

Early Steam-Powered Experiments

By the late 18th century, inventors began experimenting with steam power as an alternative to animal and human labor. Although these early attempts were rudimentary compared to the locomotives of the 19th century, they demonstrated the potential of steam engines in rail transportation.

One of the earliest examples was the work of Richard Trevithick, a British engineer who built the first steam-powered railway locomotive in 1804. Trevithick’s locomotive, operating on a short plateway in South Wales, was used to haul iron from a mine to a nearby canal. Although the locomotive successfully demonstrated the feasibility of steam power, it faced challenges such as track durability and fuel efficiency.

Another noteworthy development was the Middleton Railway in Leeds, England, which adopted steam power in 1812. The railway used twin-cylinder steam engines designed by Matthew Murray to haul coal. These early steam-powered systems marked a significant departure from animal and gravity power, paving the way for the transformative railroads of the 19th century.

The Role of Inclined Planes and Stationary Engines

Inclined planes, powered by stationary engines, were another innovative solution in pre-railroad transportation. These systems used stationary steam engines to haul carts up steep slopes via ropes or chains. The carts were either pulled directly or counterbalanced by descending carts on parallel tracks.

One prominent example was the Peak Forest Tramway in Derbyshire, England, constructed in 1796. This system featured inclined planes powered by stationary steam engines, allowing limestone to be transported from quarries to a canal. Inclined planes demonstrated the versatility of rail systems in overcoming challenging terrain and integrating multiple power sources.

Early Railroads in America

Before 1830, the United States also saw the development of railroad-like systems, particularly in the context of industrial and agricultural needs. Early American railroads were primarily used for short-distance transportation, often connecting mines, quarries, or forests to waterways or towns. The Granite Railway, built in Massachusetts in 1826, is one of the earliest examples of a railroad in the United States. Designed to transport granite from quarries in Quincy to a dock on the Neponset River, this system used horse-drawn carts traveling on iron rails.

Another notable example was the Mauch Chunk Gravity Railroad in Pennsylvania, established in 1827 to carry coal from mines to the Lehigh River. This gravity-powered railway utilized natural slopes for descending loaded cars, while animals or manual effort returned empty carts to the top. These early American railroads demonstrated the utility of guided paths and laid the foundation for the rapid expansion of the railroad network in the coming decades.

And a personal favorite example, The Delaware and Hudson Canal Company’s gravity railroad, a pioneering feat of early 19th-century engineering.Built between 1827 and 1829, this 16-mile system ingeniously utilized the force of gravity to transport coal from the mines in Carbondale, Pennsylvania, down to Honesdale, where it connected with the company’s canal. The railroad featured a series of inclined planes, each equipped with stationary steam engines to haul loaded coal cars up the steeper sections. 2 Once at the top, the cars would then coast down the inclined planes under their own weight, powered solely by gravity. This innovative approach significantly reduced the labor and costs associated with coal transportation, making it a crucial factor in the early success of the anthracite coal industry.

Full sized replica of a coal wagon used on the D&H gravity railroad to transport anthracite coal from Carbondale to Honesdale from 1828 to 1898. (Author’s photo)

Conclusion: The Foundation of Modern Railroads

The evolution of railroad-like systems before 1830 reveals a fascinating journey of innovation and adaptation. From ancient grooved trackways powered by human and animal labor to sophisticated plateways and gravity railways, these precursors laid the groundwork for the development of modern railroads. The transition from wooden to iron rails, the adoption of gravity and stationary engines, and the early experiments with steam power all contributed to the eventual emergence of steam-powered locomotives.

These early endeavors were not merely isolated experiments but vital components of the industrial revolution, enabling the efficient transportation of goods and materials. They also highlight the ingenuity of engineers and laborers who sought to overcome the limitations of existing transportation methods. By harnessing a combination of natural forces, animal power, and mechanical innovation, these pioneers created systems that would ultimately revolutionize global commerce and connectivity.

Understanding the history of railroads before railroads provides valuable insights into the incremental advancements that paved the way for one of the most transformative technologies in human history. These early systems, though rudimentary by modern standards, represent the ingenuity and determination that continue to drive technological progress today.