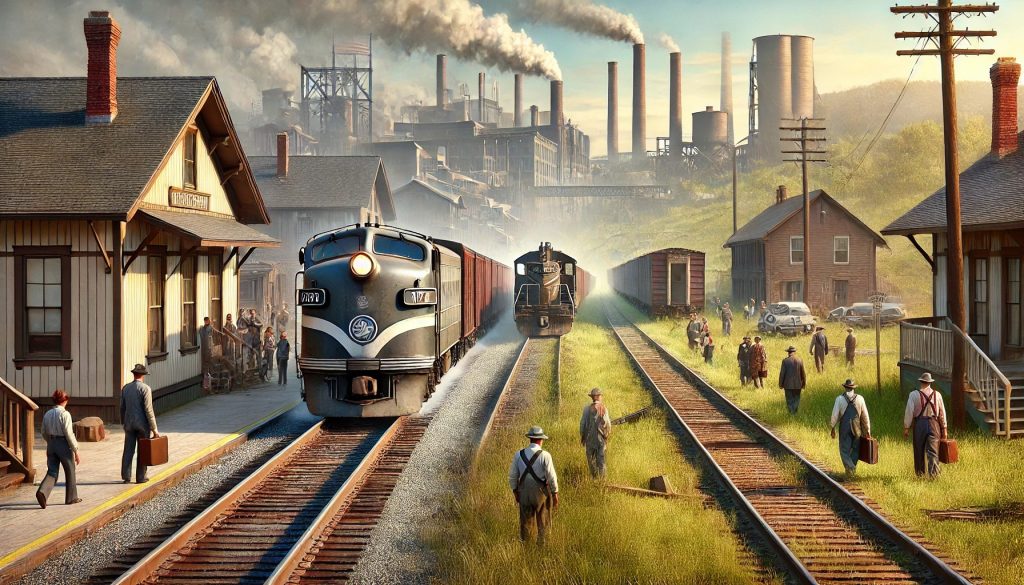

In the story of transportation, few innovations rival the transformative power of the railroad. By America’s bicentennial in 1976, the nation had witnessed the rise and fall of countless Class I railroads—industrial giants that linked cities, towns, and industries through a network of steel rails. Often called “Fallen Flags,” these railroads symbolize the industrial strength and relentless innovation of a young nation, as well as the inevitability of change in commerce and technology. But to truly understand these titans of the rail era, we must rewind the clock to the very beginning—when American railroading was still an experiment.

A nostalgic image of capturing the legacy of American railroads by the mid twentieth-century, symbolizing their peak and decline.

In railroading, a fallen flag is the term for a railroad company that has ceased to operate, either through bankruptcy, merger, acquisition, or a combination of all of these. If you were to ask any rail fan, they will all have a favorite fallen flag, sometimes more than one. For me, as you may remember, it is the Delaware and Hudson, the company my great grandfather worked for. For others with no personal connection, the attraction might be regional. Where I live, the fallen flag would be the mighty Pennsylvania Railroad. For others it might be the railroad of a favorite memory. Regardless, the connection is rooted in the memory of trains gone by.

Because fallen flags are so important to so many train enthusiasts, the Great American Railroad website features a specific section to the topic. To do that, we plan to focus on the 56 Class I railroads in the United States in 1976. A Class I railroad at that time was a designation by the Interstate Commerce Commission for railroads with a minimum operating revenue of ten million dollars. In fact, that designation was changed from $5 million to $10 million effective January 1, 1976, which dropped nine railroads to Class II

What is the significance of the year 1976? Nothing special other than my personal choice. It was the year I learned to drive and the year of our nation’s bicentennial.

The list of Class I roads was always fluid, for two reasons. The first is that railroad revenue was always in flux, growing in the early years, declining in the latter. The second reason is the aforementioned Interstate Commerce Commission’s evolving standard. By way of comparison, in 1910, the year the designation began, there were 132 Class I railroads, and the minimum operating revenue was just $1 million. In 1976, as previously stated, there were 56, but as of April 2023, just six Class I freight railroads remain.

We begin our journey of recounting the story of fallen flags by exploring some of the early railroads established in the United States. These pioneering railroads weren’t just about moving goods and passengers; they were bold ventures in engineering, commerce, and human ambition. Each one carved a unique path forward, laying the groundwork for the expansive rail networks that would come to define the American landscape. Their stories are foundational to understanding the enduring legacy of the Fallen Flags.

The First Tracks of Progress

Let’s start with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O), America’s first chartered railroad. Chartered in 1827, the B&O was created to compete with the Erie Canal for moving goods westward. It became a trailblazer in rail transportation, making history in 1830 with the “Tom Thumb,” America’s first steam locomotive. Though early skepticism surrounded steam engines, the “Tom Thumb’s” success transformed industry perceptions, proving the future of rail lay in steam power. The B&O didn’t just connect cities—it pioneered techniques in rail design, bridge construction, and locomotive engineering, turning Baltimore into a major economic hub.

In the same year, the South Carolina Canal and Railroad Company emerged as the B&O’s southern counterpart. Its locomotive, the “Best Friend of Charleston,” captured headlines as one of America’s earliest steam-powered engines. Though its tragic explosion in 1831 highlighted the challenges of early railroading, the company’s vision endured, eventually merging into the Southern Railroad and laying the groundwork for connecting Charleston with inland markets.

Meanwhile, the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company’s Gravity Railroad was exploring another angle of innovation. Designed initially to move coal via gravity, it became one of the first adopters of steam locomotives in the early 1830s. This bold move set a precedent for industrial transportation, evolving into the Delaware and Hudson Railway, a key player in the Northeast.

Then there was the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad, New York’s first chartered railroad. In 1831, its locomotive, the “DeWitt Clinton,” became a symbol of early rail travel, pulling passenger cars resembling stagecoaches. By 1853, the Mohawk and Hudson had merged into the New York Central Railroad, a powerhouse in northeastern railroading for over a century.

The Camden and Amboy Railroad, chartered the same year, bridged the critical gap between Philadelphia and New York. Its imported “John Bull” locomotive became one of America’s first operational steam engines. Over time, the railroad played a pivotal role in shaping early policies and eventually merged into the mighty Pennsylvania Railroad system.

Other railroads like the Philadelphia, Germantown, and Norristown Railroad and the New Castle and Frenchtown Railroad may have started small, but they laid crucial groundwork for the expansive systems that absorbed them. Whether serving local communities or connecting key markets, these railroads demonstrated the role of smaller lines in building larger networks.

Up in New England, the Boston and Lowell Railroad, chartered in 1835, showcased the transformative impact of railroads on industry. Connecting textile mills in Lowell to Boston’s port, it became a vital link in New England’s industrial economy before merging into the Boston and Maine Railroad.

Building a Nation, One Rail at a Time

The stories of these early railroads—each a stepping stone in the journey of American railroading—are rich with lessons in ambition, innovation, and adaptability. They remind us that the railroads we now call “Fallen Flags” were once the cutting edge of technology and commerce. Their successes and struggles paved the way for the monumental rail systems of the 20th century.

As we dive into the legacy of these Fallen Flags, we will explore the stories of how they rose to greatness and, ultimately, how they fell. From the Baltimore and Ohio to the Pennsylvania Railroad, these early ventures remind us of the ingenuity and determination that built the American railroad. Check back often as we continue to explore the history, innovation, and impact of railroads in shaping the nation. This is The Great American Railroad, and we’re just getting started.